JADE

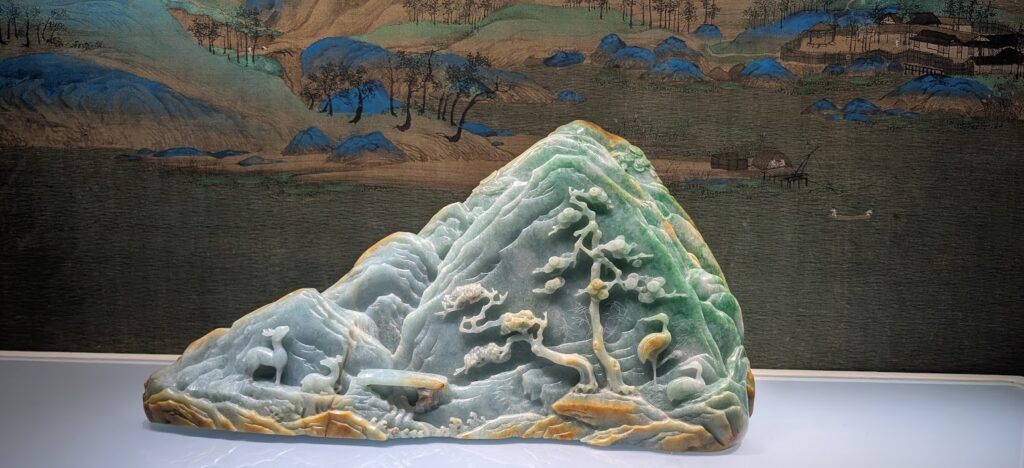

As I visited the Forbidden City Beijing, I came across a sculpture museum where nearly every piece was made from jade. My curiosity, as both a geologist and traveller, was immediately piqued. Jade—more than just the green treasure of legend—evoked images of Buddha statues, epic tales of lost artifacts that needed to be returned to its rightful location of local harmony, and a profound sense that this stone must hold remarkable significance across centuries of Asian culture. As I mused through these sculptures, I started to wonder What exactly is jade? Is it a rock, crystal, gemstone, or mineral? Why is its legend so enduring, is Jade always green? Determined to uncover its secrets, I set out to learn more.

First, let’s clarify some geological basics:

- A rock is an aggregate of one or more minerals.

- A mineral is a naturally occurring inorganic solid with a defined composition or structure.

- A crystal is a solid with atoms in a repeating pattern—most minerals can form crystals.

- A gemstone is a mineral or rock prized for rarity and beauty, often used in jewellery.

So, where does jade belong in these categories? Jade is an aggregate of minerals so it’s both a rock and a gemstone—revered for its rarity, its symbolic aura, and the stories it has carried through the ages. But jade is more complex than just a rock, it comes in two forms, distinguished by the minerals at their core:

- Jadeite (pyroxene mineral group)

- Nephrite (amphibole mineral group)

Both jadeite and nephrite tell different stories both under the microscope and across world cultures.

Jadeite forms in high-temperature, relatively low-pressure environments—usually where one tectonic plate subducts beneath another, a recipe for the birth of volcanoes and the dazzling transformation of minerals. The water-rich fluids from ocean floor sediments penetrate rocks, triggering chemical changes, especially in aluminium-rich minerals, and giving rise to jadeite. The classic regions producing jadeite—Myanmar, Guatemala, and parts of Russia—have yielded treasures in hues of emerald, green, white, lavender, yellow, brown, and even black. It was especially the emerald and “imperial” greens, coloured by trace amounts of chromium, that captured the imagination of Chinese emperors and artisans especially the Han Dynasty (206BCE–220CE), these vibrant greens adorned burial suits, ceremonial artifacts, and imperial insignias—objects believed to protect and immortalize the wearer.

Nephrite, meanwhile, is born in low pressure and relatively low temperature environments, often at tectonic boundaries where rocks undergo contact metamorphism. Its creation—through the recrystallization and alteration of amphibole minerals—results in a dense, interlocking, fibrous structure. Found in China, Russia, New Zealand, and Canada, nephrite primarily appears in shades of green, white, grey, and black. Ancient Chinese cultures, especially the Hongshan people over 7,000 years ago, began carving this softer resilient green nephrite long before jadeite’s prized hues arrived via trade. The stone’s greens symbolized heaven and virtue, and its whites and greys—much rarer—were reserved for sacred artifacts and nobility.

The toughness of nephrite meant it could be fashioned into tools, weapons, and ceremonial blades. Importantly, jade’s significance was never solely Chinese. In ancient Mesoamerica, jadeite was held in even higher esteem than gold among the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec. Mesoamerican jade objects—often deep green—were symbols of power, life, and immortality. In New Zealand, nephrite jade (locally known as pounamu) was crafted by Māori carvers into pendant hei-tiki, family weapons, and symbols of kinship, always in those telltale greens and greys.

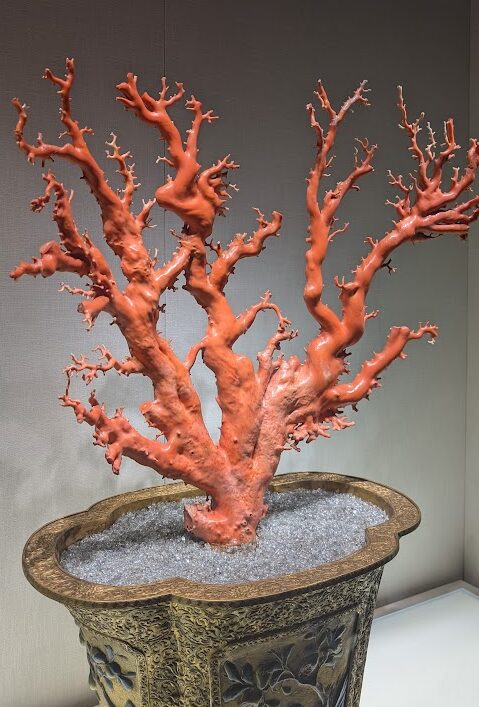

Even today, standing in the Forbidden City or browsing bustling Asian markets, one can see jade’s cultural thread still alive—bangles for protection, pendants for prosperity, heirlooms for harmony, in greens for good fortune, whites for purity, lavenders for peace, and blacks for grounding.

Jade is more than a beautiful rock—After exploring those centuries-old carvings in Beijing, my appreciation for jade has deepened: not just as a geologist drawn to its crystalline secrets, but as a traveller appreciating its tale as a symbol through the ages.